Boundaries as a Somatic Skill

“No” as a Nervous System Function

In trauma recovery, boundary work is not primarily relational or personality-based. It is regulatory. The capacity to identify, communicate, and maintain limits depends on accurate body awareness, flexible autonomic responses, and sufficient tolerance for activation. When trauma disrupts these systems, boundary distortions are predictable.

Boundaries as a Neurophysiological Process

A functional boundary requires the nervous system to:

Detect internal signals (interoception)

Differentiate self from other

Assess safety (neuroception)

Mobilize assertive energy without escalating into fight/flight

Maintain connection without collapsing into shutdown

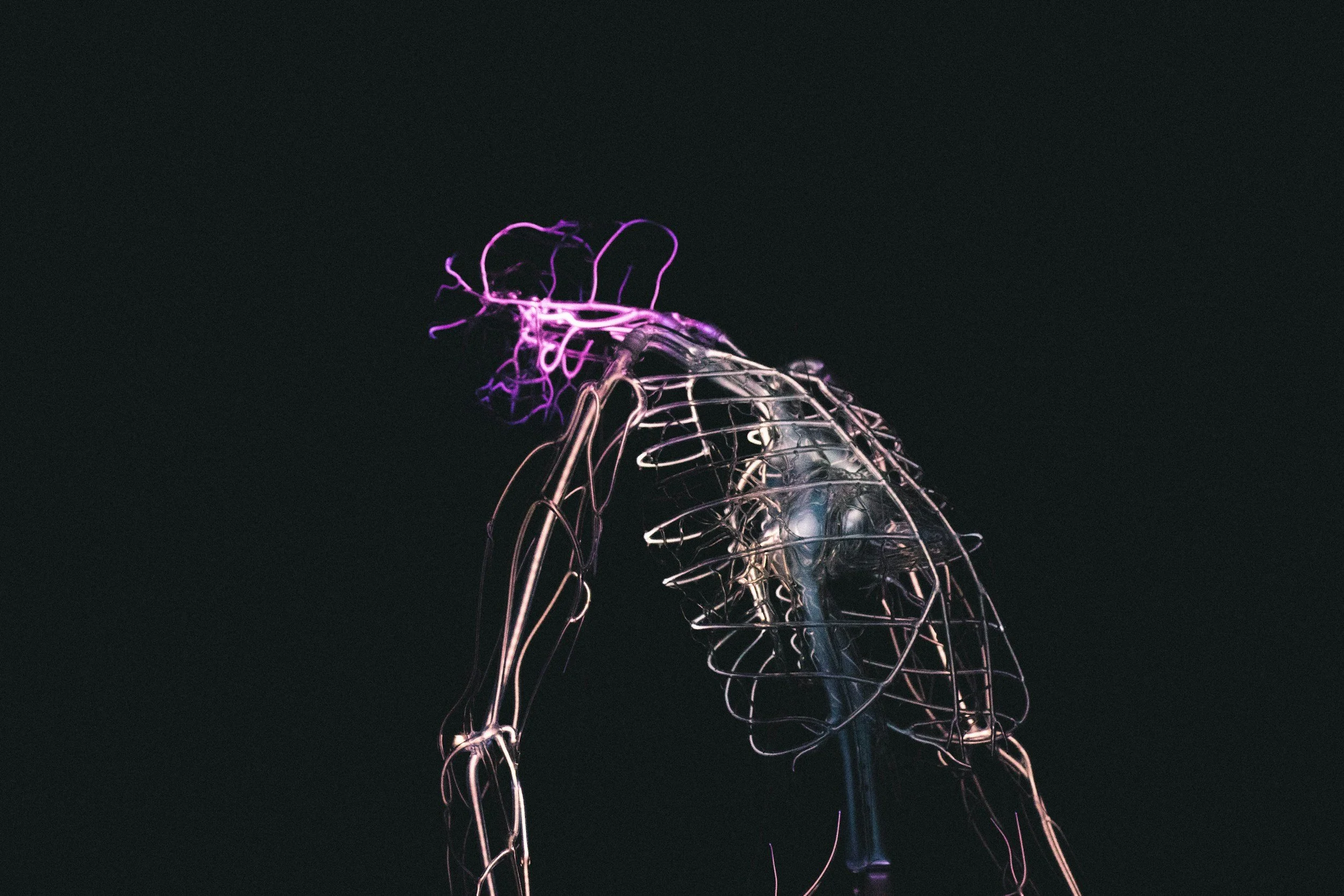

These processes rely on coordinated activity between the insula (interoceptive awareness), prefrontal cortex (executive function), and autonomic pathways described in polyvagal theory.¹ ² Trauma alters these networks. As a result, boundary impairment is common.

Common Boundary Distortions in Trauma

1. Reduced Interoceptive Accuracy

Research shows trauma can impair interoceptive processing.¹ When internal signals are unclear, limits are difficult to identify. Observable patterns:

Recognizing discomfort only after prolonged exposure

Agreeing to requests followed by delayed resentment

Fatigue after social interaction without clear cause

Difficulty distinguishing anxiety from obligation

Early boundary work often involves restoring access to subtle internal cues.

2. Narrowed Window of Tolerance

Effective boundary-setting requires regulated sympathetic mobilization.³ If arousal exceeds capacity:

Boundaries may become abrupt or aggressive.

If arousal drops below capacity:

Verbal assertion becomes difficult or impossible.

Trauma narrows the window of tolerance, reducing flexibility under stress.³ Boundary calibration therefore includes expanding regulatory range.

3. Conditioned Fawn or Compliance Responses

In environments where attachment depended on appeasement, autonomic strategies may prioritize relational safety over self-protection.⁴ Physiological indicators:

Breath restriction during agreement

Constriction in throat or diaphragm

Increased heart rate paired with smiling or nodding

Rapid verbal agreement followed by somatic tension

The boundary signal is present but overridden.

4. Persistent Defensive Activation

Chronic violation can sensitize threat detection systems.² Indicators:

Muscular bracing at minor disagreements

Escalation to anger disproportionate to stimulus

Rapid cutoff behaviors

Inability to tolerate ambiguity

In these cases, boundary work involves modulation rather than strengthening.

The Felt Sense of a Boundary

Boundaries are first detected as physiological shifts. Common markers:

Posterior shift in posture

Subtle diaphragmatic tightening

Heat in face or neck

Gastric contraction

Increased muscle tone in shoulders or jaw

Developing awareness of these signals is a foundational skill in trauma-informed regulation work.

Specific Somatic Interventions for Boundary Rehabilitation

Interoceptive Differentiation Training

Track internal states during low-stakes decisions. Compare:

Full-body “yes” (expansive breath, steady heart rate)

Compliance-based “yes” (restricted breath, tension)

Documenting patterns increases neural integration and signal clarity.¹

Regulated Assertion Practice

In neutral contexts, practice stating preferences while monitoring arousal:

“I’m unavailable at that time.”

“That does not work for me.”

Observe heart rate, breath, and muscle tone. If arousal spikes, pause and return to baseline before continuing. The objective is assertion within regulatory capacity.

Micro-Delay Conditioning

Introduce a one-breath pause before responding to requests. This disrupts automatic compliance and strengthens executive regulation.

Behavioral Enforcement

Boundaries require congruent action.

Examples:

Ending conversations when dysregulation escalates

Limiting frequency of contact

Declining tasks without over-explanation

Adjusting physical proximity

Consistent follow-through reinforces autonomic learning that protective behavior is effective.

Post-Assertion Tracking

After boundary expression, observe:

Changes in respiration

Residual sympathetic activation

Dorsal collapse indicators (fatigue, heaviness)

Return to baseline

Mixed activation (relief + anxiety) is common during recalibration.

Why Boundary Work Is Foundational in Trauma Healing

Without reliable boundary function:

Chronic stress responses persist

Attachment reenactments continue

Autonomic instability remains unaddressed

Interpersonal strain accumulates

Boundary capacity reflects integration between interoception, regulation, and relational engagement. Improvements are observable physiologically: steadier respiration, proportional mobilization, faster return to baseline, and increased tolerance for relational complexity. Boundary development is therefore not a personality adjustment. It is measurable nervous system reorganization.

-

Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn894

-

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

-

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind. Guilford Press. https://www.guilford.com/books/The-Developing-Mind/Daniel-Siegel/9781462520674

-

an der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Viking. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/313065/the-body-keeps-the-score-by-bessel-van-der-kolk-md/

Trauma Isn’t a Thought Problem:

Trauma is not primarily a thinking problem — it is a nervous system prediction problem. This science-based article explores how trauma healing, somatic therapy, and bottom-up trauma therapy work through nervous system regulation, predictive processing, and neuroplasticity. Learn how the brain updates safety through the body, grounded in neuroscience and clinical research.

Why “Bottom-Up” Healing Works (and What Your Brain Has to Do With It)

When people begin exploring trauma healing, the assumption is often straightforward: if we can understand what happened, reframe the story, and think differently about it, symptoms should resolve. Insight should create relief.

Except it often doesn’t.

Many people can clearly articulate their trauma history, recognize behavioral patterns, and hold accurate narratives — yet still experience hypervigilance, shutdown, chronic tension, or emotional reactivity. The mind understands the story. The nervous system may still be operating from older protective predictions. Cognitive understanding and physiological regulation often shift on different timelines. This gap exists because trauma is not primarily a thinking problem. It is a nervous system prediction problem.

The Brain Predicts Before It Thinks

The nervous system is designed to prioritize survival. Subcortical regions involved in threat detection — including the amygdala, brainstem, and autonomic nervous system — evaluate safety before conscious interpretation occurs. Joseph LeDoux’s research demonstrates that sensory information can activate defensive responses milliseconds before cortical processing assigns meaning or context.¹ In practical terms: the body reacts first. The story comes later.

Contemporary neuroscience increasingly describes the brain as a predictive system rather than a reactive one. Karl Friston’s predictive processing framework explains that perception, emotion, and action aim to minimize prediction error — the gap between what the brain expects and what the body senses.² When trauma occurs, predictive models become biased toward danger. Sensory cues, internal states, or relational signals that once coincided with threat may continue to trigger protection even when present conditions are safe. This explains why trauma responses often persist long after the original event has ended and why understanding trauma and the brain requires looking beyond conscious thought.

Why Insight Alone Often Plateaus

Cognitive processes primarily engage cortical regions responsible for language, reasoning, and narrative organization. These systems support meaning-making but do not directly recalibrate autonomic reflex patterns.

Declarative memory (“what happened”) and procedural memory (“how the body learned to respond”) operate through distinct neural pathways. Trauma-related learning frequently resides in implicit systems governing muscle tone, breathing, visceral sensation, and orienting responses.³

You cannot think your way out of a reflex any more than you can reason your way out of a knee jerk.

This helps explain why insight may increase understanding without reliably shifting physiological reactivity — a key consideration for anyone exploring nervous system regulation, somatic therapy, or bottom-up trauma therapy.

What “Bottom-Up” Means in Plain Terms

“Bottom-up” refers to information traveling from the body to the brain — sensation, movement, breath, and physiological state shaping neural prediction. “Top-down” works in the opposite direction: thoughts and interpretations influencing bodily response. Both pathways operate continuously. Trauma primarily alters bottom-up signaling, making sensory and physiological input central to recalibration. From a neuroplasticity perspective, repeated sensory experiences that contradict threat predictions gradually reshape neural networks. Structural brain imaging research confirms that training and repeated experience can alter gray matter organization over time.⁴

Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory describes how autonomic state influences emotional regulation, social engagement capacity, and perceptual bias. Physiological regulation increases access to flexible cognitive processing, highlighting the bidirectional relationship between body and brain.⁵ This provides biological grounding for why how trauma is stored in the body remains clinically relevant.

Learning, Plasticity, and Safety

Learning is state-dependent. Memory consolidation, emotional updating, and behavioral flexibility depend on nervous system conditions that support plasticity. Chronic stress physiology narrows this flexibility and reinforces rigid prediction loops.⁶

When the nervous system repeatedly experiences regulated safety, prediction error decreases and expectations update. Reflexive responses soften, emotional range broadens, and behavioral options expand. These mechanisms are measurable within established neuroplasticity and stress physiology research. This framework helps contextualize why body-based approaches continue to appear in trauma outcome literature.⁷ For individuals seeking somatic trauma therapy in Kansas City, or exploring evidence-informed approaches to healing trauma without talk therapy, the neuroscience clarifies what is changing beneath subjective experience.

Summary

Trauma reflects a nervous system shaped by protective predictions formed under threat. Bottom-up approaches align with established principles of sensory-driven learning, predictive updating, and autonomic regulation. As physiological patterns stabilize, cognitive and emotional flexibility often follow. For communities interested in trauma healing in Kansas City, the neuroscience of trauma, and applied models of somatic therapy, current evidence increasingly supports embodied learning as a central mechanism of long-term nervous system change.

-

1. LeDoux, J. (1996).

The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Simon & Schuster.

Foundational work on fast subcortical threat processing (“low road”) and emotional circuitry.

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Emotional-Brain/Joseph-LeDoux/9780684836599 -

2. Friston, K. (2010).

The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

Primary framework describing predictive processing and error minimization in the brain.

https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn2787 -

3. Squire, L. R., & Dede, A. J. O. (2015).

Conscious and unconscious memory systems. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(3).

Explains declarative vs procedural memory systems and implicit learning mechanisms.

https://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/content/7/3/a021667 -

4. Draganski, B., et al. (2004).

Neuroplasticity: Changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature, 427, 311–312.

Demonstrates experience-dependent structural brain change.

https://www.nature.com/articles/427311a -

5. Porges, S. W. (2011).

The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. W.W. Norton.

Autonomic regulation model linking physiological state with emotional and social functioning.

https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393707007 -

6. McEwen, B. S., & Morrison, J. H. (2013).

The brain on stress: Vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14, 1–14.

Explores how chronic stress impacts neural plasticity and regulation capacity.

https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn3381 -

7. Payne, P., Levine, P. A., & Crane-Godreau, M. A. (2015).

Somatic experiencing: Using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6.

Clinical discussion of bottom-up sensory mechanisms in trauma treatment.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00093/full

Play Is a Nervous System Experience

Explore how play regulates the nervous system through Polyvagal Theory, the window of tolerance, and embodied safety — and why play supports trauma recovery.

In the context of nervous system regulation and trauma healing, play isn’t just a metaphor —

it’s a biological experience. Bodies register play through the autonomic nervous system (ANS), engaging mechanisms that promote safety, social connection, and functional flexibility rather than survival defense. These physiological effects of play are rooted in our neurobiology, particularly through pathways described by Polyvagal Theory and the concept of the window of tolerance.

Play and the Social Engagement System

Central to Polyvagal Theory — a framework developed by neuroscientist Stephen Porges — is the idea that mammals evolved a specialized branch of the vagus nerve that supports safe social interaction and physiological regulation. This is often called the ventral vagal system, part of what some researchers describe as the social engagement system, which links facial expression, vocalization, attention, and autonomic state into a coordinated network geared toward safety and connection.

When the ventral vagal pathways are active, the body is more capable of calm engagement and flexibility. Activities that stimulate face-to-face interaction, gentle movement, rhythm, and shared attention — many hallmarks of play — engage these circuits. These patterns of activation signal safety beneath conscious awareness, lowering defensive states and making regulation more accessible. Unlike cognitive reassurance — “I know I’m safe” — these physiological cues are processed through what Porges calls neuroception: the nervous system’s subconscious evaluation of safety in the environment.

Window of Tolerance and Play

Another neuroscience-informed concept relevant here is the window of tolerance, a model that describes the range of nervous system activation in which a person can function effectively — emotionally, cognitively, socially, and physically. Inside that window, the nervous system can adapt to stressors without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down. Outside it, people may experience hyperarousal (anxiety, panic, defensiveness) or hypoarousal (numbness, dissociation).

Play tends to expand this window by allowing the nervous system to experience manageable shifts in activation in the presence of safety, predictability, and social engagement. Through repeated cycles of activation and recovery — such as laughing, movement, anticipation, pause, and cooperation — the system gains lived experience of returning to regulation. Over time, these experiences can broaden the range of inputs the nervous system can tolerate before tipping into dysregulation.

Play as Bodily Feedback, Not Just Fun

This perspective reframes play from being “just enjoyable” to being a form of physiological input. Through cues like rhythmic movement, facial expression, vocal tone shifts, and reciprocal engagement, play provides the kind of bottom-up sensory feedback that the nervous system uses to calibrate regulation. In other words, play is how the body practices safety. When nervous systems lack safe, patterned experience, regulation becomes harder; when they have repeated patterns of safe activation and recovery, regulation becomes easier.

This helps explain why many people find that structured, serious interventions help their understanding but don’t fully shift how they feel in their bodies. The body learns through experience — not just explanation.

-

Polyvagal Theory: A Science of Safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience (Porges, 2022).

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227/full -

Polyvagal Institute overview of Polyvagal Theory.

https://www.polyvagalinstitute.org/whatispolyvagaltheory -

Explanation of the Window of Tolerance (Psychology Today).

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/making-the-whole-beautiful/202205/what-is-the-window-of-tolerance-and-why-is-it-so-important

Play As a Nervous System Intervention

Explore how play functions as a nervous system intervention in trauma healing, supporting regulation, flexibility, and physiological safety through somatic principles.

Trauma isn’t “just in your head.” It lives in the body

— specifically in how the nervous system organizes defense responses long after a stressor has passed. When the body repeatedly perceives threat without sufficient safety or recovery, protective survival responses (fight, flight, freeze) can remain active even in non-threatening situations. This chronic autonomic activation contributes to anxiety, emotional dysregulation, and a restricted ability to engage socially or experience pleasure. Neurological research shows these patterns are not primarily cognitive; they are rooted in physiological processes that require experience, not just insight, to change.

The Nervous System and Regulation

Central to autonomic regulation is the vagus nerve, a major component of the parasympathetic nervous system that helps slow heart rate and promote recovery after stress. Healthy vagal function — often indexed by heart rate variability (HRV) — is correlated with better emotional and physiological regulation. Research links altered vagal regulation with childhood adversity and chronic stress, suggesting that how the nervous system responds to challenge is a critical component of long-term psychological and physical health.

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, while debated in some neuroanatomical details, offers a widely used framework for understanding how autonomic states support social engagement or defensive survival responses. It emphasizes that physiological safety — not just cognitive belief in safety — is necessary for regulation and connection.

Why Play Matters

Play may seem “light,” but it involves dynamic physiological patterns that are exactly what a dysregulated nervous system needs to retrain itself. Play naturally mixes:

Activation — through movement and novelty

Recovery — through safe end points and social engagement

This cycle allows the autonomic nervous system to experience manageable activation followed by return to calm, thereby strengthening its flexibility. Some practitioners describe this as “exercising the vagal brake,” meaning play helps the nervous system learn how to shift between states of arousal and regulation more fluidly.

While most research on play’s effects comes from developmental studies — showing that free play is linked with improved baseline vagal tone in children — the physiological mechanisms (activation followed by recovery through safe engagement) are not exclusive to childhood. Similar pathways underlie adult nervous system regulation, even if the form of play looks different.

Takeaway

Play is not recreational fluff — it’s a biological experience that contributes to autonomic regulation by repeatedly providing safe activation and recovery. As a nervous system intervention, it supports flexibility, recovery after stress, and stronger social engagement pathways.

-

Free social play in children predicts higher levels of respiratory sinus arrhythmia (a marker of parasympathetic/vagal activity), suggesting play supports autonomic regulation.

Gleason, T. et al. (2021). Opportunities for free play and young children’s autonomic regulation.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34196394/ -

Reviews associations between early adversity and vagal functioning, indicating alterations in autonomic regulation linked with stress exposure.

Systematic review on childhood adversity and vagal activity.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763422004092 -

Polyvagal Theory describes vagal tone (as indexed by RSA) as a physiological marker of parasympathetic regulation relevant to social engagement and stress response.

Polyvagal theory (summary).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyvagal_theory -

Heart rate variability (HRV), including RSA measures, is widely used in psychophysiological research to index cardiac vagal (parasympathetic) influence and self-regulatory capacity.

Laborde, S., et al. (2017). Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiology.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00213/full -

In an animal study, natural play behavior elevated HRV (a marker of parasympathetic activation) during and immediately after play, signaling a positive autonomic effect of play behavior in mammals.

Steinerová, K. (2025). Play behavior increases heart rate variability in pigs.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11812062/ -

Play supports learning, exploration, social skills, and emotional development, including neural pathway integration — foundational concepts relevant to nervous system processes.

Learning through play. Wikipedia overview.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_through_play