Somatic Therapy Is Everywhere -What the Research Is Saying

Somatic therapy is increasingly used in trauma healing, coaching, and nervous system regulation. This evidence-based article reviews current research on somatic trauma therapy, explains how body-based approaches work, and outlines how to identify legitimate somatic training versus trend-based marketing. Designed for readers seeking scientifically grounded information on trauma-informed somatic practices and provider education standards.

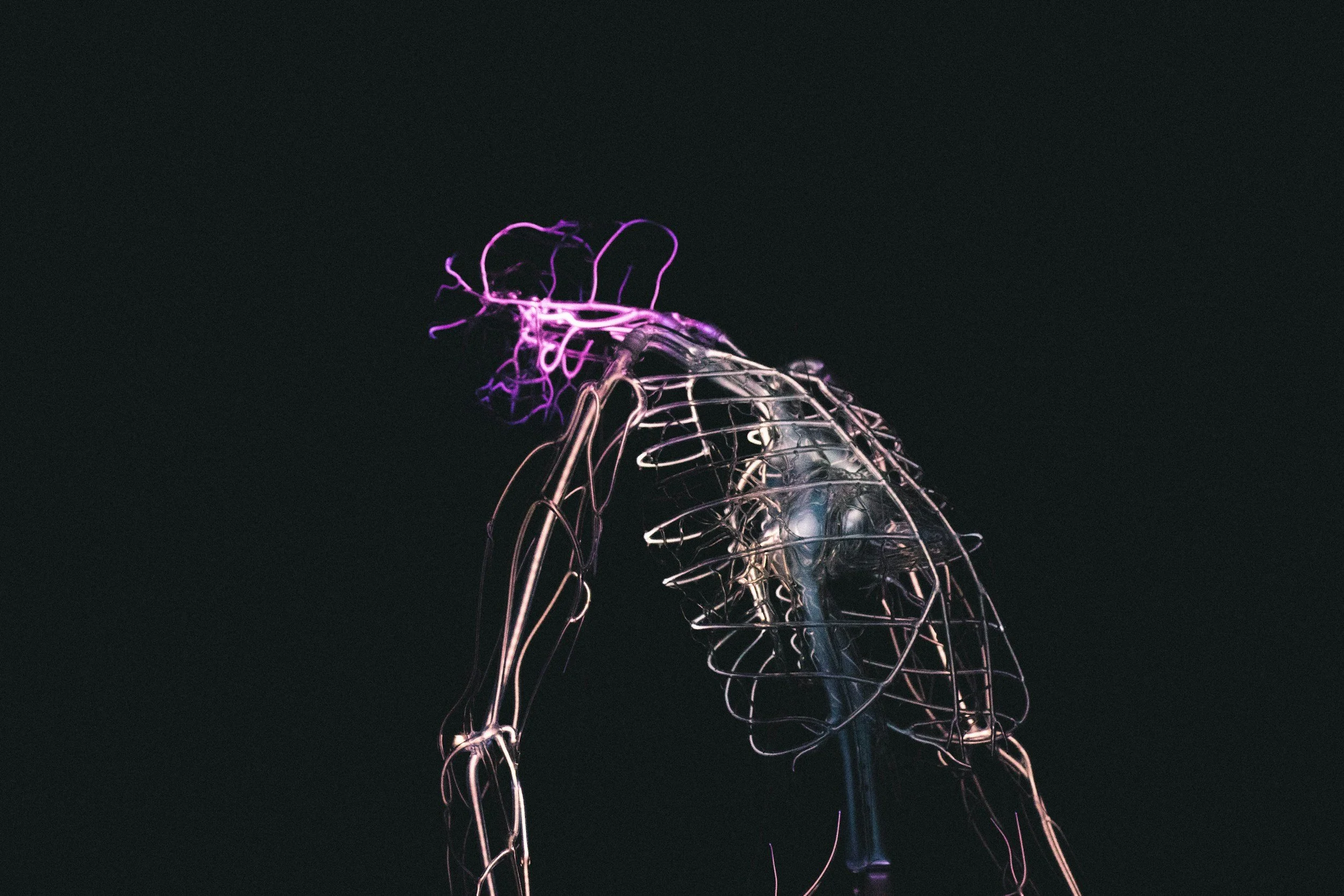

Somatic therapy refers to a group of body-centered approaches

used in trauma and stress healing that emphasize the role of bodily sensation, movement, and nervous system responses in recovery.

As somatic language becomes more widespread — including in coaching, wellness marketing, and social media — it’s important to be able to distinguish evidence-based trauma healing practice from trend-driven use of terminology. This article presents the science behind somatic trauma approaches and practical criteria for identifying substantive practice.

What Somatic Trauma Healing Is — According to Evidence

Somatic trauma approaches are grounded in the idea that traumatic experiences can be expressed and influenced by the body’s physiological responses. Unlike traditional talk-only methods that focus on cognition alone, somatic practice engages physical sensation and regulatory systems as part of the healing process. This aligns with neuroscience models of embodied stress response, which suggest trauma can become “held” in patterns of autonomic activation and somatic response. ([turn0search4][turn0search21])

Two well-defined approaches with theoretical and training frameworks are:

Somatic Experiencing (SE): A body-oriented method developed for trauma physiology that focuses on tracking and regulating physical sensations linked to threat and stress responses. ([turn0search13])

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (SP): A comprehensive approach integrating somatic awareness with emotional and cognitive processing for trauma-related distress. ([turn0search5])

Other recognized somatic frameworks include Hakomi Mindful Somatic Psychotherapy, which integrates mindfulness with somatic principles, and body-psychotherapy traditions that inform trauma work. ([turn0search1][turn0search30])

What the Research Actually Shows

The research on somatic trauma interventions is emerging and nuanced, varying in volume and rigor by method.

1. Evidence for Somatic Experiencing ®(SE)

Preliminary controlled trials suggest that SE may reduce symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and improve affective and somatic well-being. Early evidence shows positive effects for PTSD symptoms relative to control conditions, with participants reporting reductions in distress. ([turn0search0][turn0search2][turn0search35])

2. Evidence on Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (SP)

SP is conceptually supported by embodied trauma theory and is included in somatic education and training programs. While research literature is not as extensive as for cognitive-behavioral therapies, SP is recognized within somatic trauma training curricula and clinical discourse. ([turn0search5][turn0search30])

3. Broader Somatic Mechanisms

Independent research on interoception and embodied processing suggests body-based awareness relates to regulation of physiological responses and emotional experience. These findings support the theoretical rationale for somatic engagement in trauma care, though mechanistic support does not substitute for clinical outcome evidence. ([turn0search21][turn0search28])

4. General Field Status

Leading health sources describe somatic therapy as promising but still less established in research volume (in terms of large randomized trials) compared with some standard trauma therapies like exposure-based cognitive approaches. ([turn0search4][turn0search3])

In summary, somatic trauma healing methods have scientific foundations and preliminary evidence supporting their use, particularly for PTSD-related symptoms, but research is still in development. Claims of universal effectiveness are not supported by the current state of controlled clinical research.

Why Somatic Language Is Popular

Interest in somatic trauma healing has expanded for several reasons:

Broader cultural adoption of nervous system and body-mind language, which resonates with people’s lived experiences of stress and trauma.

Increased visibility of somatic framework training — including programs for both clinicians and non-clinical practitioners.

Marketing use of somatic terminology in coaching, wellness, and bodywork without consistent grounding in trauma science.

This popularity makes it important to distinguish legitimate training and evidence-informed practice from surface-level branding.

How to Spot Legitimate Trauma-Focused Somatic Practice

As somatic terminology becomes more visible across healthcare, education, and wellness spaces, identifying whether a provider or training pathway reflects substantive trauma-informed practice — rather than surface-level marketing — requires attention to training structure, theoretical grounding, and connection to evidence.

1. Training Pathways With Published Theoretical and Clinical Literature

Some somatic methodologies have published peer-reviewed literature examining theoretical models and clinical outcomes. Examples include:

Somatic Experiencing® (SE) — a body-oriented trauma approach with randomized and observational studies evaluating effects on trauma-related symptoms.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (SP) — an integrative somatic psychotherapy model with published theoretical frameworks and emerging clinical research.

Hakomi Mindful Somatic Psychotherapy — a long-standing somatic psychotherapy model with formalized theory and academic literature supporting its principles.

These programs articulate clear physiological models, structured curricula, and defined clinical competencies that can be evaluated through published sources.

In addition to these programs that have published peer-reviewed research supporting their theoretical models and clinical outcomes, there are also established educational institutions that provide rigorous training in somatic and embodiment-based methodologies grounded in neuroscience, attachment theory, and experiential learning, even though they have not yet produced independent clinical outcome studies in the academic literature.

Examples include:

Somatica Institute®

The Embody Lab

Strozzi Institute for Somatics

These institutions offer structured educational pathways, faculty oversight, and curricula informed by contemporary somatic theory and applied practice, while not positioning themselves as research-producing clinical treatment models.

2. Clear Scope of Practice and Ethical Boundaries

Providers should:

Describe why they use somatic concepts in trauma work.

Outline limits of their scope (e.g., coaching vs clinical treatment).

Offer transparent training histories rather than generic “somatic” marketing language.

If a provider’s description is vague, buzzword-heavy, or focused on immediate transformation claims without clear training or context, that may indicate trend usage rather than evidence-informed practice.

3. Connection to Published Research and Frameworks

Legitimate practitioners reference existing studies, established models (e.g., SE, SP) and openly acknowledge where evidence is strong versus emerging. A credible practice will differentiate preliminary evidence from unverified claims.

Summary

Somatic trauma healing refers to methods that integrate bodily awareness and nervous system engagement into trauma recovery. Formalized programs like Somatic Experiencing®, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, and Hakomi Mindful Somatic Psychotherapy have theoretical structures and preliminary research support, though the overall evidence base is still developing. Somatic terminology has grown rapidly in broader coaching and wellness spaces; discerning substantive trauma-focused practice from surface-level use of somatic language requires attention to training quality, theory grounding, scope transparency, and connection to existing evidence.

-

Brom, D., Stokar, Y., Lawi, C., Nuriel-Porat, V., Ziv, Y., & Lerner, A. (2017). Somatic Experiencing for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Outcome Study.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5518443/ -

Kuhfuß, M., et al. (2021). Somatic Experiencing – Effectiveness and Key Factors of a Body-Oriented Approach: A Scoping Review.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8276649/ -

Khalsa, S. S., et al. (2018). Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap. Healthcare (MDPI).

https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/13/11/1258 -

Harvard Health Publishing. (2023). What Is Somatic Therapy?

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-somatic-therapy-202307072951 -

Somatic Experiencing® International. (n.d.). SE™ Professional Training Program.

https://traumahealing.org/professional-training/ -

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute. (n.d.). Training and Curriculum Overview.

https://sensorimotorpsychotherapy.org/ -

Hakomi Institute. (n.d.). Mindful Somatic Psychotherapy Training Programs.

https://hakomiinstitute.com/ -

Somatica Institute. (n.d.). Somatic and Trauma-Informed Coaching Education.

https://www.somaticainstitute.com/ -

The Embody Lab. (n.d.). Integrative Somatic Trauma Therapy & Embodiment Training Programs.

https://www.theembodylab.com/ -

Strozzi Institute for Somatics. (n.d.). Somatic Coaching and Embodied Leadership Training.

https://strozziinstitute.com/

Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy for PTSD:

Explore the science behind psychedelic-assisted therapy for PTSD, what’s clinically proven, what’s emerging, and why self-guided use carries real risks.

What’s Real, What’s Emerging, and What’s Not for DIY

Psychedelic-assisted therapy has rapidly moved from fringe research into mainstream clinical conversation.

Substances such as MDMA, psilocybin, and ketamine are now being studied — and in some cases legally used — as adjuncts to psychotherapy for treatment-resistant PTSD and trauma-related conditions. The early data is promising, and the cultural excitement is understandable.

At the same time, public enthusiasm often outpaces nuance. Online conversations frequently frame psychedelics as shortcuts to healing or self-guided tools for trauma processing. Trauma physiology, however, does not respond well to shortcuts. Altered states amplify nervous system activity — for better or worse — making context, containment, and regulation essential. Understanding what psychedelic-assisted therapy actually involves helps separate legitimate clinical progress from oversimplified hype.

Why Psychedelics Are Being Studied for Trauma

PTSD is increasingly understood as a nervous system condition rather than a purely cognitive disorder. Trauma alters threat detection, emotional regulation, stress hormone activity, memory processing, and relational safety. These adaptations persist long after the original danger has passed, which explains why insight alone rarely resolves trauma symptoms. Certain psychedelic substances temporarily alter how the brain processes fear and emotional salience. Neuroimaging research shows reduced activity in the amygdala alongside increased connectivity across brain networks, allowing traumatic material to be accessed with less defensive activation and greater emotional flexibility.

MDMA increases oxytocin and serotonin while dampening fear responses, enabling trauma memories to be revisited with reduced physiological overwhelm in controlled clinical settings. Psilocybin appears to increase neural plasticity and disrupt rigid cognitive patterning, supporting shifts in perception and meaning-making. Ketamine can interrupt entrenched depressive and trauma loops through transient dissociative effects when paired with therapeutic integration. These substances are not considered curative on their own. They function as catalysts within structured psychotherapy.

What “Real” Psychedelic Therapy Includes

Legitimate psychedelic-assisted therapy involves medical screening, psychological assessment, trauma-informed clinicians, structured preparation, and post-session integration. The therapeutic impact comes from how the altered state is held, interpreted, and translated into regulated nervous system learning. Decades of trauma research consistently demonstrate that healing emerges through safety, relational attunement, and regulated embodiment — not intensity alone. Psychedelics may temporarily expand emotional access, but without integration, insights often remain fragmented or destabilizing.

What’s Still Emerging

Research continues to refine dosing protocols, contraindications, therapist training standards, and long-term outcomes. Legal frameworks and access models are evolving unevenly by region. There is growing interest in combining psychedelic work with somatic and attachment-based models, which aligns with modern trauma neuroscience emphasizing bottom-up regulation and embodied safety. However, training pathways and ethical standards are still developing, making careful discernment increasingly important for both clinicians and clients.

Why Psychedelics Are Not a DIY Trauma Tool

Self-guided psychedelic use for trauma carries meaningful risks. Psychedelics lower psychological defenses and can rapidly surface traumatic material without sufficient containment. For individuals with developmental trauma, dissociation, or attachment injury, this can overwhelm rather than regulate the nervous system. Integration is a neurobiological process that requires stabilization after activation. Without skilled co-regulation and therapeutic framing, symptoms such as anxiety, depersonalization, and emotional flooding can intensify rather than resolve. Medical, dosage, legal, and substance purity risks further complicate unsupervised use. From a nervous system perspective, sustainable healing depends on titration — gradual capacity building — rather than flooding the system with intensity.

The Larger Context

Psychedelic-assisted therapy represents a legitimate and evolving frontier in trauma treatment. The science is real. The potential is meaningful. The outcomes depend entirely on container quality, clinical skill, and nervous system safety. Altered states may open access. Integration determines whether healing actually occurs. Trauma healing with psychedelics in Kansas City is still being scrutinized as conversations continue.

-

Mitchell, J. M., Bogenschutz, M., Lilienstein, A., et al. (2021).

MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD:A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nature Medicine, 27(6), 1025–1033.

Why this matters: This is the landmark Phase 3 clinical trial demonstrating statistically significant PTSD symptom reduction using MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. -

Mitchell, J. M., et al. (2023).

MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: Confirmatory Phase 3 trial results. Nature Medicine / PubMed.

Why this matters: Confirms efficacy and safety across multiple sites and supports FDA review and expanded clinical legitimacy. -

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R. (2011 / updated review).

The therapeutic potential of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: Mechanisms of action and clinical context. Psychopharmacology / PubMed Central.

Why this matters: Excellent mechanistic explanation of how MDMA impacts fear processing, emotional openness, and therapeutic engagement — bridges neuroscience and clinical application. -

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – National Center for PTSD.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy for PTSD: Clinical Overview.

Why this matters: Government-level synthesis of evidence, risks, and clinical context from one of the largest trauma research institutions in the world.https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/txessentials/psychedelics_assisted_therapy.asp

-

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. J. (2019).

REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews.

Why this matters: Foundational neuroscience model explaining how psychedelics alter predictive coding, rigid belief systems, and neural flexibility — highly relevant to trauma theory and nervous system learning.

Empirical Support and Clinical Implications

Review research on play, stress recovery, vagal tone, somatic therapy outcomes, and clinical safety — exploring how play supports nervous system regulation and trauma healing.

The idea that play supports nervous system regulation isn’t just philosophical —

there’s meaningful evidence across animal research, human physiology studies, and trauma-treatment outcomes suggesting that play and play-like states can support recovery, flexibility, and social engagement (with important caveats about safety and context).

Animal research: play and stress recovery

In affective neuroscience, Jaak Panksepp identified PLAY as a primary emotional system in mammals, emphasizing that play is not “extra,” but biologically organized and evolutionarily conserved. Play is also consistently studied as a key driver of social learning and adaptive development. For example, research on juvenile rats shows that depriving animals of normal peer play can lead to socio-cognitive deficits in adulthood and measurable changes in prefrontal cortex neurons — a finding that links play to brain development in circuits relevant to flexibility and regulation. A major review of social play in rats describes play as rewarding and deeply tied to motivational and neurobiological systems, reinforcing that play is not simply a behavior but a neurophysiological process with downstream effects.

Human physiology: stress hormones, regulation, and play-like states

Direct adult “play” studies using HRV and cortisol are still emerging, but there is stronger evidence for play-adjacent states that involve the same ingredients: spontaneity, social engagement, laughter, and positive affect. A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis in PLOS ONE found that spontaneous laughter is associated with greater reductions in cortisol compared with usual activities, supporting the idea that playful affect can shift stress physiology. (This doesn’t mean all play reduces stress — some play can be stimulating, competitive, or physiologically activating — but it does support that specific playful states can measurably downshift stress hormones.)

Somatic therapy outcomes

On the trauma-treatment side, there is published outcome data for somatic approaches. A randomized controlled study on Somatic Experiencing ® (SE) reported significant improvements in PTSD symptoms and depression compared to controls, suggesting SE can be effective for trauma-related symptoms. A separate scoping review found preliminary evidence of positive effects of SE on PTSD-related symptoms, while also emphasizing the need for more high-quality studies.

Clinical implications and contraindications

Clinically, “play as intervention” works best when it is voluntary, titrated, and recoverable — meaning it doesn’t push the nervous system past capacity. Play can become dysregulating when it is coercive, overly intense, shame-based, or socially unsafe. For trauma histories involving boundary violations, clinicians typically prioritize consent, choice, and pacing before introducing higher activation forms of play.

Takeaway:

the evidence supports play as biologically meaningful, potentially stress-buffering, and compatible with somatic trauma treatment — but the type of play and the nervous system context determine whether it becomes regulating or overwhelming.

-

Panksepp, J. (2010). Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind. (Open access)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3181986/ -

Pellis, S. M. & Pellis, V. C. (2023). Play fighting and the development of the social brain. PubMed record

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36621585/ -

Vanderschuren, L. J. M. J. et al. (2016). The neurobiology of social play and its rewarding value in rats. (Open access)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5074863/ -

ramer, C. K. et al. (2023). Laughter as medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis of laughter interventions on cortisol. PLOS ONE.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0286260 -

Brom, D. et al. (2017). Somatic Experiencing for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A randomized controlled outcome study. (Open access)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5518443/

PubMed record: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28585761/ -

Kuhfuß, M. et al. (2021). Somatic experiencing – effectiveness and key factors… a scoping literature review. (Abstract page)

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/20008198.2021.1929023

Full record (repository): https://tandf.figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Somatic_experiencing_effectiveness_and_key_factors_of_a_body-oriented_trauma_therapy_a_scoping_literature_review/14963382

Play Is a Nervous System Experience

Explore how play regulates the nervous system through Polyvagal Theory, the window of tolerance, and embodied safety — and why play supports trauma recovery.

In the context of nervous system regulation and trauma healing, play isn’t just a metaphor —

it’s a biological experience. Bodies register play through the autonomic nervous system (ANS), engaging mechanisms that promote safety, social connection, and functional flexibility rather than survival defense. These physiological effects of play are rooted in our neurobiology, particularly through pathways described by Polyvagal Theory and the concept of the window of tolerance.

Play and the Social Engagement System

Central to Polyvagal Theory — a framework developed by neuroscientist Stephen Porges — is the idea that mammals evolved a specialized branch of the vagus nerve that supports safe social interaction and physiological regulation. This is often called the ventral vagal system, part of what some researchers describe as the social engagement system, which links facial expression, vocalization, attention, and autonomic state into a coordinated network geared toward safety and connection.

When the ventral vagal pathways are active, the body is more capable of calm engagement and flexibility. Activities that stimulate face-to-face interaction, gentle movement, rhythm, and shared attention — many hallmarks of play — engage these circuits. These patterns of activation signal safety beneath conscious awareness, lowering defensive states and making regulation more accessible. Unlike cognitive reassurance — “I know I’m safe” — these physiological cues are processed through what Porges calls neuroception: the nervous system’s subconscious evaluation of safety in the environment.

Window of Tolerance and Play

Another neuroscience-informed concept relevant here is the window of tolerance, a model that describes the range of nervous system activation in which a person can function effectively — emotionally, cognitively, socially, and physically. Inside that window, the nervous system can adapt to stressors without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down. Outside it, people may experience hyperarousal (anxiety, panic, defensiveness) or hypoarousal (numbness, dissociation).

Play tends to expand this window by allowing the nervous system to experience manageable shifts in activation in the presence of safety, predictability, and social engagement. Through repeated cycles of activation and recovery — such as laughing, movement, anticipation, pause, and cooperation — the system gains lived experience of returning to regulation. Over time, these experiences can broaden the range of inputs the nervous system can tolerate before tipping into dysregulation.

Play as Bodily Feedback, Not Just Fun

This perspective reframes play from being “just enjoyable” to being a form of physiological input. Through cues like rhythmic movement, facial expression, vocal tone shifts, and reciprocal engagement, play provides the kind of bottom-up sensory feedback that the nervous system uses to calibrate regulation. In other words, play is how the body practices safety. When nervous systems lack safe, patterned experience, regulation becomes harder; when they have repeated patterns of safe activation and recovery, regulation becomes easier.

This helps explain why many people find that structured, serious interventions help their understanding but don’t fully shift how they feel in their bodies. The body learns through experience — not just explanation.

-

Polyvagal Theory: A Science of Safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience (Porges, 2022).

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227/full -

Polyvagal Institute overview of Polyvagal Theory.

https://www.polyvagalinstitute.org/whatispolyvagaltheory -

Explanation of the Window of Tolerance (Psychology Today).

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/making-the-whole-beautiful/202205/what-is-the-window-of-tolerance-and-why-is-it-so-important

The Body Learns Through Experience, Not Insight

Learn how the nervous system changes through experience, neuroplasticity, implicit memory, and somatic learning — and why insight alone often can’t resolve trauma.

In trauma healing, one of the most common misunderstandings-

is the belief that insight alone rewires the nervous system. While talk therapy and cognitive processing can be helpful for understanding one’s story, the nervous system doesn’t reorganize based solely on words or analysis. Instead, it changes through experience — repeated sensory, relational, and motor experiences that create new neural patterns and embodied safety.

Neuroplasticity: Experience Shapes the Brain

The brain’s ability to change in response to experience — known as neuroplasticity — is one of the most well-established findings in modern neuroscience. According to research on activity-dependent plasticity, neural circuits remodel themselves in response to use and experience, allowing new pathways to form while underused ones diminish. This biological mechanism underlies learning, memory formation, motor skill acquisition, and recovery after injury. Norman Doidge’s influential work The Brain That Changes Itself provides numerous examples of how repeated behavioral practice can reorganize brain function, from recovery of motor abilities to changes in sensory perception. In the context of trauma, these findings suggest that experiential practices — not just cognitive insight — are necessary to shape how the nervous system responds to stress and safety.

Implicit Memory and Procedural Learning

Not all memory is conscious. Implicit memory refers to learning that occurs without explicit awareness, shaping behavior and physiological responses without requiring conscious recall. Procedural memory — a subtype of implicit memory — allows us to perform actions automatically (like riding a bike), even when we can’t verbally explain how we do it. This distinction matters for trauma because much of the nervous system’s survival responses are stored implicitly. A person may verbally understand that a situation is safe, yet their body continues to respond as if danger is present because the procedural memory networks governing those responses have not yet been updated through experience. Embodied practices directly access these implicit and procedural systems in ways that talk alone cannot. like:

movement

breathwork

interoceptive awareness

sensory engagement

Why Talk Therapy Can Plateau

Cognitive approaches primarily engage explicit memory systems — facts, meanings, and narratives. These systems are consciously accessible but have limited influence over subcortical networks responsible for visceral, motor, and autonomic regulation. In other words, understanding something intellectually doesn’t guarantee that the body’s survival pathways have been changed. Somatic therapies reverse this imbalance by engaging bottom-up processes. By directing attention to interoceptive (internal sensation), proprioceptive (body position), and kinesthetic (movement) information, these approaches create new embodied experiences that can be encoded into memory at a nervous system level.

Experience + Safety: A Learning Pair

For neuroplastic changes to occur in the context of trauma, repeated experience must be paired with safety. Research on learning mechanisms shows that the nervous system forms stronger, more lasting adaptive connections when novel experiences are introduced in safe, regulated contexts. While much of this work comes from general learning science, its implications for trauma recovery are clear: the nervous system learns through patterned repetition — and safety is the context in which beneficial patterns take hold.

Takeaway

Trauma healing, from a somatic perspective, isn’t about uncovering more insight. It’s about creating new embodied experiences that teach the nervous system — at a procedural, implicit level — what safety feels like. Over time, these experiences can rewire threat pathways and expand the body’s capacity for regulation, connection, and choice.

-

Explains how neural circuits physically change in response to repeated experience, forming the biological foundation of learning and behavior change.

Source:

Activity-dependent plasticity. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activity-dependent_plasticity -

Documents real clinical cases showing how repeated sensory and behavioral experience reshapes brain organization and function.

Source:

Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain That Changes Itself.

Overview: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Brain_that_Changes_Itself -

Defines implicit memory and explains how learning occurs outside conscious awareness — critical for understanding trauma and nervous system learning.

Source:

Implicit memory. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Implicit_memory -

Demonstrates how cognition and learning are rooted in bodily experience and sensory-motor systems rather than abstract thought alone.

Source:

Foglia, L., & Wilson, R. A. (2013). Embodied Cognition. Frontiers in Psychology.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00323/full -

Explores how bodily awareness and interoception influence emotional regulation, learning, and neural processing.

Source:

Khalsa, S. S., et al. (2018). Interoception and Mental Health. Biological Psychiatry.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006322318317406 -

Explains how procedural memory systems encode skills and patterns through repetition rather than conscious thought.

Source:

Procedural memory. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Procedural_memory

Play As a Nervous System Intervention

Explore how play functions as a nervous system intervention in trauma healing, supporting regulation, flexibility, and physiological safety through somatic principles.

Trauma isn’t “just in your head.” It lives in the body

— specifically in how the nervous system organizes defense responses long after a stressor has passed. When the body repeatedly perceives threat without sufficient safety or recovery, protective survival responses (fight, flight, freeze) can remain active even in non-threatening situations. This chronic autonomic activation contributes to anxiety, emotional dysregulation, and a restricted ability to engage socially or experience pleasure. Neurological research shows these patterns are not primarily cognitive; they are rooted in physiological processes that require experience, not just insight, to change.

The Nervous System and Regulation

Central to autonomic regulation is the vagus nerve, a major component of the parasympathetic nervous system that helps slow heart rate and promote recovery after stress. Healthy vagal function — often indexed by heart rate variability (HRV) — is correlated with better emotional and physiological regulation. Research links altered vagal regulation with childhood adversity and chronic stress, suggesting that how the nervous system responds to challenge is a critical component of long-term psychological and physical health.

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, while debated in some neuroanatomical details, offers a widely used framework for understanding how autonomic states support social engagement or defensive survival responses. It emphasizes that physiological safety — not just cognitive belief in safety — is necessary for regulation and connection.

Why Play Matters

Play may seem “light,” but it involves dynamic physiological patterns that are exactly what a dysregulated nervous system needs to retrain itself. Play naturally mixes:

Activation — through movement and novelty

Recovery — through safe end points and social engagement

This cycle allows the autonomic nervous system to experience manageable activation followed by return to calm, thereby strengthening its flexibility. Some practitioners describe this as “exercising the vagal brake,” meaning play helps the nervous system learn how to shift between states of arousal and regulation more fluidly.

While most research on play’s effects comes from developmental studies — showing that free play is linked with improved baseline vagal tone in children — the physiological mechanisms (activation followed by recovery through safe engagement) are not exclusive to childhood. Similar pathways underlie adult nervous system regulation, even if the form of play looks different.

Takeaway

Play is not recreational fluff — it’s a biological experience that contributes to autonomic regulation by repeatedly providing safe activation and recovery. As a nervous system intervention, it supports flexibility, recovery after stress, and stronger social engagement pathways.

-

Free social play in children predicts higher levels of respiratory sinus arrhythmia (a marker of parasympathetic/vagal activity), suggesting play supports autonomic regulation.

Gleason, T. et al. (2021). Opportunities for free play and young children’s autonomic regulation.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34196394/ -

Reviews associations between early adversity and vagal functioning, indicating alterations in autonomic regulation linked with stress exposure.

Systematic review on childhood adversity and vagal activity.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763422004092 -

Polyvagal Theory describes vagal tone (as indexed by RSA) as a physiological marker of parasympathetic regulation relevant to social engagement and stress response.

Polyvagal theory (summary).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyvagal_theory -

Heart rate variability (HRV), including RSA measures, is widely used in psychophysiological research to index cardiac vagal (parasympathetic) influence and self-regulatory capacity.

Laborde, S., et al. (2017). Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiology.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00213/full -

In an animal study, natural play behavior elevated HRV (a marker of parasympathetic activation) during and immediately after play, signaling a positive autonomic effect of play behavior in mammals.

Steinerová, K. (2025). Play behavior increases heart rate variability in pigs.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11812062/ -

Play supports learning, exploration, social skills, and emotional development, including neural pathway integration — foundational concepts relevant to nervous system processes.

Learning through play. Wikipedia overview.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_through_play